Typical ‘Double Creole Quarters’ on Laurel Valley Sugar Plantation in Thibodaux, LaFourche Parish, Louisiana.(Library of Congress Digital Archives https://www.loc.gov/resource/hhh.la0202.photos/?sp=3)

Eva Reed

By Olivia Warren

Name of interviewee: Eva Reed

Age at emancipation: 2 years old

’Race’: Black

Year of interview: 1940

Place of interview: McDonoghville

State of interview: Louisiana

Place of enslavement (there may be more than one): LaFourche Parish, Louisiana

Address of interviewee (if given): 308 Monroe Street

‘Occupation’: Sharecropper and later Domestic

‘Occupation’ of mother: Sharecropper

‘Occupation’ of father: Sharecropper

Size of slaveholding unit: Unknown

Name of enslaver (there may be more than one): Unknown

Name of plantation/farm: Unknown

Crop produced on slaveholding unit: Likely Sugar

Name of interviewer: Flossie McElwee

Race of interviewer: White

Is this included in Rawick’s supplement series?: No

Is there evidence of editing: No, but it is possible

Eva Reed was born in the LaFourche Parish region of Louisiana in 1863, to Louisiana-born parents Perry and Letta Elles. When reflecting on her life with Louisiana Writers’ Project interviewer, Flossie McElwee, at her home in 1940, Eva narrates her experience both as a young woman working the fields of LaFourche, and later as a domestic worker in New Orleans. Born during the Civil War, of which she stresses she has no recollection, and just two years prior to the emancipation of 1865, Eva’s testimony provides a valuable insight into life beyond war and slavery, as a Black woman of the first post-emancipation generation.

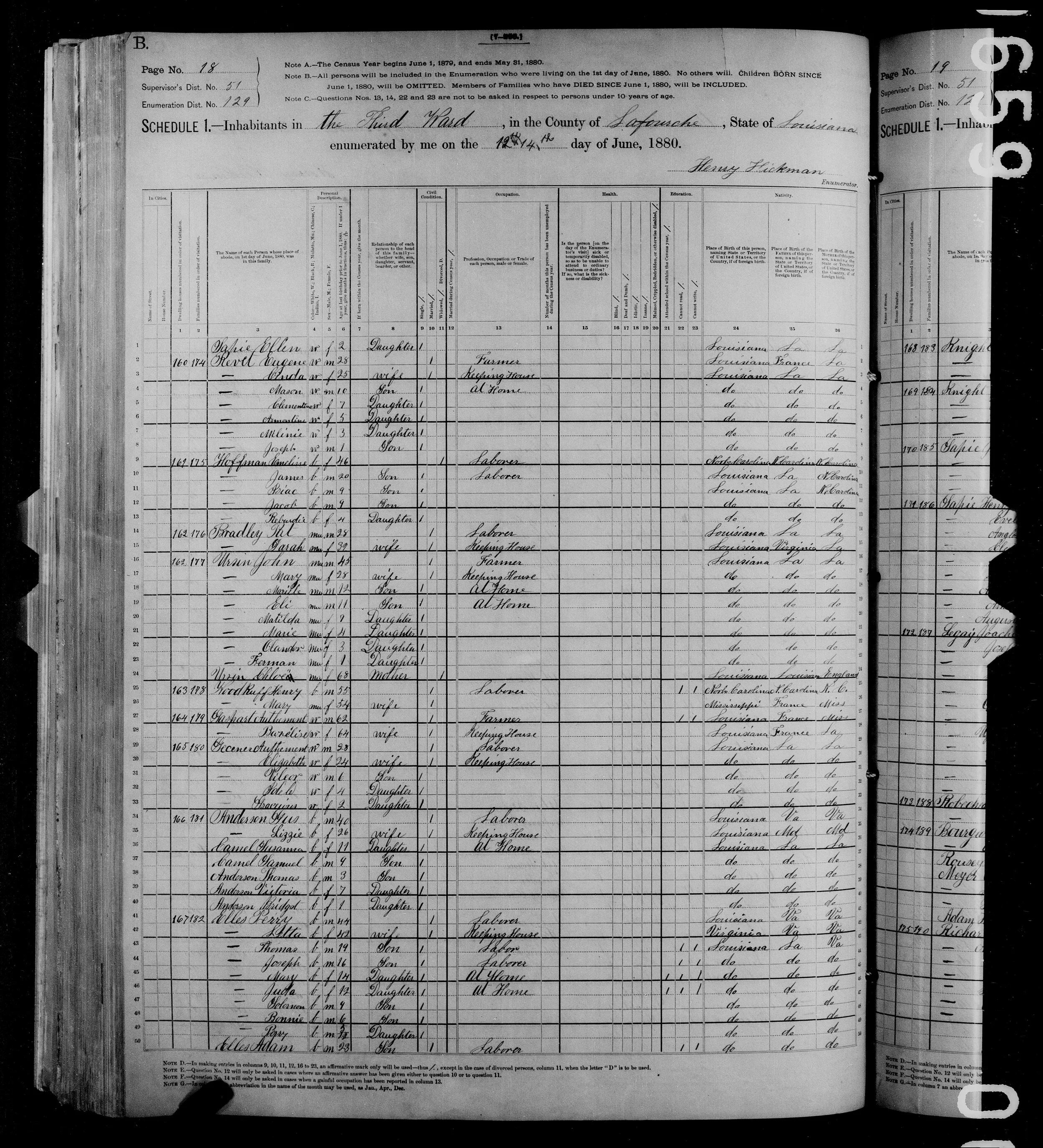

Formed in 1807, LaFourche parish was one of many sugar parishes located in south Louisiana that relied heavily on the labour of Black enslaved people. Though not classed as enslaved, Eva notes that during her youth, both she and her family farmed as sharecroppers; a process by which tenant families rented plots from landowners in return for a percentage of their crop. Following the Civil War, the practice of sharecropping grew in popularity in the southern states as it afforded freedmen a degree of independence far-removed from slavery, and enabled landowners to return their land to production. Studies have shown that postbellum Louisiana possessed the second highest percentage of sharecroppers in all states surveyed, and so that Eva and her family were among them is unsurprising.[i] However, it was not until 1920 that censuses in the United States designated ‘sharecropper’ as a profession, and so information concerning the landowner and land rented by Eva’s family is not readily available.[ii] This might also explain why an 1880 census of 3rd Ward, LaFourche, simply lists Eva’s father and brothers as ‘labourers’. Equally ambiguous is a 1900 census, which places Eva and her husband, Henry Reed, at Ward 6 of LaFourche and designates their occupations as ‘day labourer’. What the census does reveal is that after marrying in 1892, Eva and her husband stayed in LaFourche for some years before moving to McDonoghville.

Although no reference is made to it within the interview, it is likely that Eva was living and working in the LaFourche region during the Thibodaux Massacre of 1887. On 23rd November, an organised group of Black sugar cane workers protested their severe working conditions and meagre pay, leading to a reactionary massacre inflicted by the all-white state militia. Approximately 60 Black people were killed in the shooting and were buried in unmarked graves. Eva makes no reference to this violence, or any reference to poor treatment at the hands of the white people for that matter: “All the white folks is good to me”. Whether there is truth in this statement is unclear, but it is certainly possible that Eva felt compelled to give a favourable account of her relationships with white people due to the fact that Flossie McElwee, her interviewer, was white. It is also important to consider that many of the Federal Writers’ Project interviews collected between 1935-41 were subject to editing if they were deemed too inflammatory. There is no definitive evidence that Eva’s interview was edited, but her probable feelings of unease when telling her story to a white interviewer means that her account should be still be viewed with caution.

The primary theme of Eva’s narrative is her religious faith. Eva recalls a personal encounter she had with God in the potato fields of LaFourche, during which both Heaven and Hell were revealed to her. Eva’s connection and loyalty to her Baptist faith, and Jesus, is apparent throughout the interview in the form of songs and prayers. She mentions that at 76 years of age, she can no longer attend church, but her pastor still visits her home. According to the WPA’s Louisiana Historical Records Survey, there were over 330 Baptist churches in New Orleans in 1941, highlighting the prevalence of the Baptist faith in New Orleans during Eva’s lifetime.

It was in McDonoghville, New Orleans, that Eva began working as a domestic for white families and she appears to remember it fondly. Although she was tested by some employers, who would place money in shoes to see if she stole, she recalls that she was paid reasonably. She also notes that she was often rewarded with food and other items in return for her service. By 1940, the exact year that Eva’s interview took place, 60 percent of Black women worked in domestic roles across America.[iii] While her vocation was not unusual, her appreciative recount of it contrasts the conclusion reached by Mary Anderson, Director of the Women’s Bureau of United States Department of Labour, in 1938 that “domestic service was the least standardised of American vocations”.

Eva does not mention when she moved to McDonoghville, but a 1940 city directory shows that her husband was still living with her, at 308 Monroe St., when the interview took place. Whether Eva was asked to be interviewed without her husband, or opted to do so herself, remains unclear.

It has not been possible to find a photograph of Eva, but the interview alone reveals her incredible strength of character. Despite suffering with diabetes and an amputated leg, she rejoices that she still keeps her own house and cooks on crutches. She talks fondly of visits from the children of her final employer, Miss Cushman, who call her ‘Old Reece’, and the determination of her faith. Her narrative, along with so many others collected by the Federal Writer’s Project, ensures that the experiences of the formerly enslaved and the postbellum generation are not lost in history.

[i] Garrett Jr., Martin A., Xu, Zhenhui, ‘The Efficiency of Sharecropping: Evidence from the Postbellum South’, Southern Economic Journal, Vol. 69, No. 3 (Jan 2003), pp. 578-595

[ii] Woodman, Harold D., ‘Post-Civil War Southern Agriculture and the Law’, Agricultural History, Vol. 53, No. 1 (Jan 1979), pp. 319-337

[iii] Wooten, Melissa E., Branch, Enobong H., ‘Defining Appropriate Labour: Race, Gender, and Idealization of Black Women in Domestic Service’, Race, Gender & Class, Vol. 19, No. 3/4 (2012), pp. 292-308

Bibliography

Geneologytrails.com: http://genealogytrails.com/lou/lafourche/census.html

Historic American Engineering Record, Library of Congress Digital Collections: https://www.loc.gov/collections/historic-american-buildings-landscapes-and-engineering-records/

Miliken, Genevieve, ‘The Religious Landscape of New Orleans’, Online. Available https://www.arcgis.com/apps/Cascade/index.html?appid=b3a2f898c0ac49819c6faf09e9d80603

Myheritage.com: https://www.myheritage.com/research?s=889594361