Liverpool and the Confederacy: Social Links and Dialogues

By James Houghton (MA Modern History, LJMU)

In this blogpost, James Houghton discusses just a small part of his research on Liverpool’s social links to the Confederacy in the antebellum and Civil War era.

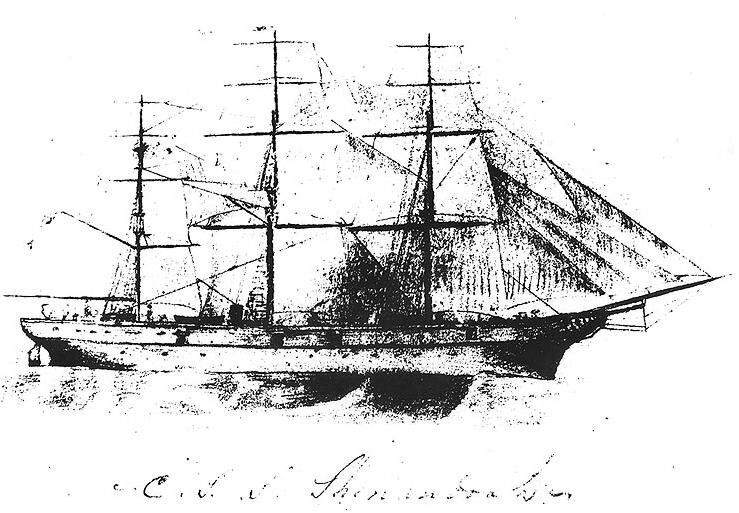

On 7 November 1865, the Liverpool Mercury reported on the arrival of the C.S.S Shenandoah into the River Mersey. The Mercury reported, ‘considerable excitement was caused on "Change" yesterday morning by circulation of the report that the Confederate cruiser Shenandoah… was passed about 8 o'clock by the steamer Douglas at anchor at the bar, of Victoria Channel, apparently waiting for high water.’[i] The Shenandoah was a Confederate war vessel that saw action during the American Civil War, garnering a notoriety for its capturing and sinking of 38 Union vessels during the war’s lifetime. American President Andrew Johnson announced the Civil War’s end on 9 May 1865, however the Shenandoah’s Captain Waddel was oblivious to the announcement and continued preying upon Union ships in the Atlantic. Upon Waddel’s discovery of the Confederacy’s defeat, he bound Shenandoah for Liverpool knowing that returning to US’ shores would see him, and his crew trialled for piracy. The Mercury continues, ‘since the defeat of the South the flag of the Confederation has been seldom, if ever, seen in the Mersey. As might be expected, therefore, the appearance of a steamer in the river flaunting the Palmetto excited considerable attention…’[ii]

After two days, Captain Waddel and his crew were given parole in Liverpool, whilst the Shenandoah was detained by the British Government. This event became memorialised within local folklore, with Liverpool boasting itself as the site of the American’s Civil War last act. As somebody from Merseyside, I have been retold this story several times by other locals.

The Shenandoah event demonstrated the economic ties Liverpool had with the Confederacy, which by the 1860s were grounded in the mass importation of cotton into Liverpool. This blogpost will set out just some of my research that goes beyond economic explanations of why Liverpool traded and publicly sided with the Confederacy. I examine the social interactions of both Liverpudlians and Confederate Americans to develop a more-rounded explanation of why they sought each other out during the American Civil War. As an example, the Mercury listed Confederate flags being flown in the Mersey as a common occurrence during the war. However, even past the war’s conclusion, Liverpudlians still showed sympathies towards the defeated Confederates. A follow-up summary in the 9 November Liverpool Mercury explains that, ‘on Tuesday one of the Southern merchants in Liverpool volunteered to send on board the Shenandoah a supply of provisions… The vessel continues to be an object of curiosity to crowds of people on the banks of the river, and to passengers on board the ferry steamers.’[iii] A simplified economic explanation would conclude that any ties with the Confederacy would be severed upon its defeat, yet the Shenandoah not only sailed into the Mersey but was given provisions by its residents.

Louisianan William Palfry and travel accounts to Liverpool

Confederate perceptions on Liverpudlian culture and society can best be articulated through travel accounts from southern Americans. Let us consider the writings of Henry William Palfrey. Henry was born into the mercantile Palfrey family, who eventually became split between Massachusetts and Louisiana branches. Henry established himself in New Orleans after serving in the War of 1812 between Britain and the United States, as a cotton merchant and slave owner.[iv] Henry was an adamant proponent for slavery, which caused friction between the two Palfrey branches.’[v]

Henry staunchly defended slavery and dealt in cotton, siding with the Confederacy for the Civil War’s entirety. He visited Liverpool after being assigned the American Commissioner to the 1855 World Fair in Paris. Writing to his family on 15 July 1855, Henry remarked

‘here I am at last in the great Commercial City of Liverpool. I am so overcome with astonishment at the scenes around me that I cannot realise the fact of being here…’[vi]

Liverpool’s reputation proceeded itself to Henry, who described it in sparkling terms. Henry continues by making special mention of Liverpool’s docks. Historian Sven Beckert comments that Liverpool’s wonder was not in its beauty, who quotes an account attributing ‘hideousness’ to the city, and that ‘the chief objects of attraction in Liverpool are, decidedly, the spacious Docks…’[vii] A far cry from Henry’s account, which praises both the dock’s efficiency and magnificence. ‘We entered the Harbour this morning – a beautiful day and beautiful sight… such sights and novelties it is useless for me to attempt a description… They have thousands of ships mixed up in magnificent docks, mixed up with splendid stores and warehouses 6 or 7 stories high.’[viii]

Palfry’s observations of Liverpool come across positively glistening, a sentiment reinforced in a reply to Henry’s letters: ‘Uncle Henry has seen and done and enjoyed so much while he was gone, and come back so enchanted with Europe, that he says he would like to spend all his leisure time there as long as he lives…’[ix] The cities that Palfry visited enthralled him, Liverpool included. Whilst a single case study, this account demonstrates an entertaining dialogue being relayed into a communal conscious that paints Liverpool in the positives that Palfry deemed important. A beautiful city, with an impressive dockyard infrastructure and mercantile possibilities.

Through Palfry’s letters we can see how, to an enslaver, military veteran, and an American Commissioner, a sparkling account of Liverpool might influence like-minded individuals - especially when the prospect of Civil War was becoming evident, and allies were being sought. David Hepburn Miller notes as such whilst covering Civil War espionage between the Confederacy and the Union, in which again Liverpool’s dockyards are praised for their beauty and practicality. Miller cites Herman Melville’s 1849 Redburn as further influencing Confederate attitudes and perceptions towards Liverpool. ‘”The extent and solidity of these Structures, seemed equal to what I had read of the old pyramids… the docks of Liverpool, even at the present day surpass all others in the world”… It was here that the South had determined to construct a modern navy.’[x] Redburn, a semi-autobiography piece of adventure fiction, painted Liverpool and crucially its dockyard infrastructure as stupendous. David Seed has argued, ‘the fact remains that Redburn gives the most detailed account of Liverpool dockland life in the nineteenth-century fiction… assumed there was an interested readership, especially in America…’[xi] Amongst both American public and private circles, Liverpool was being applauded for its splendour and sizeable dockyard services and was thus selected to construct the Confederacy’s naval infrastructure.

James Dunwoody Bulloch, Confederate spy and tasked with procuring ships for the Confederacy whilst in Liverpool

Fraser, Trenholm & Company

During the Civil War, Fraser, Trenholm & Company was owned by American born George Alfred Trenholm. Loy establishes Trenholm as ‘possibly the richest man in the Confederacy, with interests in steamships, railroads, wharves, banks, hotels, cotton presses, plantations, and slaves. He was, by any measure, a pillar of southern and Charlestonian moneyed society…’[xii]

Loy contends that ultimately business motivations trumped patriotic ideologies in Trenholm’s decision to support the Confederacy, which involved turning his Liverpool firms into shipbuilding enterprises. Whilst I would not argue economic drivers were not a factor, letters between the Trenholm family indicate a more slave-centric motivation. In a June 1865 letter, Trenholm’s son William reveals concerns shared between him and his incarcerated father that enslaved people could face extinction if freed. William Trenholm wrote that ‘[t]he negroes will be, by degrees, crowded into the working districts, as the Indians were driven… and that they will slowly become extinct. In the meanwhile we shall suffer for lack of labour… Cotton planting on the Atlantic… is done forever – prices will cease to be quoted in Liverpool…’[xiii] Trenholm’s dialogue reads almost apocalyptically, reflecting a notion that the Trenholm’s were fighting to conserve slavery in order to continue exploiting enslaved people for cotton manufacturing.

Whilst the root of this motivation is still business-led, William’s belief that black people would go extinct without white overseers highlights a ‘white man’s burden’ dimension to the Trenholm’s wartime participation.[xiv] Business motivations drove the Trenholms to participate, but at the root of those motivations was slavery and racial hierarchical connotations and justifications affiliated with slavery.

Charles Prioleau, also of Fraser, Trenholm and Company, and influenced by a friendship with the Confederate spy James Dunwoody Bulloch and personal southern affiliations, pathed the way for the construction at Birkenhead of Confederate cruisers like the CSS Florida. Prioleau’s motivations have been perceived as economic[xv], yet through his records there are traces of his personal values and how they related to the Confederate cause. A purely economic motive to side with the Confederacy would infer Prioleau, along with Trenholm, to distance themselves from the Confederacy when profit began to fall. Therefore, Prioleau’s and Trenholm’s own beliefs need to be considered to demonstrate why they personally invested so much into an ailing effort.

In Prioleau’s case, there were religious connections to his South Carolina home. A series of letters sent to Prioleau from Charleston’s Anglo-Catholic Church of Holy Communion highlight that Prioleau funded the restoration of Charleston’s St. Michael’s Church that was damaged during the war. A letter from the Church’s Rector A. Turner Porter who describes himself as Prioleau’s friend, relays Church news following a Union attack. ‘A friend, who takes the liberty of writing, in hopes that it will give you some pleasure to hear our brave old city, though beleaguered with Yankee armies… is not wholly fallen to fear, or war.’[xvi] This correspondence demonstrates Prioleau’s personal investment in the war, one founded in his Anglo-Catholic beliefs. Prioleau, an influential figure in establishing Confederate naval capabilities, did so out of economic drive coupled with a figurative and literal attack on his religion. Prioleau was able to channel the lucrative profit generated in Liverpool into restoring his spiritual home.

Porter’s letter highlights a friendship founded between Prioleau and himself, founded on restoring a war-weary church. Porter’s writing continues, listing another influential figure in preserving Charleston’s Church of Holy Communion, George A. Trenholm. ‘Our mutual friend in George A. Trenholm has provided me, as the Rector of the Church of the Holy Communion with a very fine lot in Rutledge Creek…’[xvii] Trenholm is associated as another Holy Communion friend, giving refuge to the Pastor away from war-torn Charleston. Both Prioleau and Trenholm, business-led merchants, demonstrate that religion and personal faith featured in their business-motivated war efforts.

Through this analysis, we can go beyond previously established catch-all definitions of profit-led motivations being the primary factor in Prioleau’s and Trenholm’s Confederate motivations. We can understand how one of Liverpool’s largest mercantile firms continued heavily investing in a losing war effort, that ultimately bankrupted said firm. Personal factors of religion and the desire to maintain slaves drove Fraser, Trenholm & Company into irrelevancy, as the firm could have pulled out when the Civil War’s outcome was becoming increasingly apparent. Instead, Prioleau and Trenholm used their Liverpool assets that flourished during the conflict to support a failing secession out of a sense of religious duty.

Liverpool’s Confederate links are curious in how they manifested and how they are remembered. Now over a hundred-and-fifty years detached from the American Civil War, any sense of proslavery associations has been communally memory-holed. Jessica Moody discusses how Liverpool portrays itself ‘beating’ other slave ports in its eighteenth century domination of the transatlantic trade in enslaved people, [xviii] yet similarly, Liverpool has established its nineteenth-century Confederate legacy as a quirk in the city’s history. Regarding how Liverpool’s ties and dialogues with the Confederacy should be remembered today, a re-evaluation is required that casts the four years of fuelling a war effort as not simply a footnote. Hundreds of thousands died in the American Civil War, a conflict with slavery at its centre. Liverpool sided with the secessionists that fought to keep black Americans in slavery. For a city that has been described as cemented with African blood, the gravitas of the matter should not be reduced to a mere point of interest in Liverpool’s history.

[i] ‘THE CONFEDERATE CRUISER SHENANDOAH IN THE MERSEY’, 7 November 1865, Liverpool Mercury, British Library Newspapers, Source: https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=BNCN&u=livjm&id=GALE|BB3204083580&v=2.1&it=r&sid=BNCN&asid=f23c98d0 (accessed 8 February 2021).

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] ‘THE SHENANDOAH’ 9 November 1865, Liverpool Mercury, British Library Newspapers, Source: https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=BNCN&u=livjm&id=GALE|BB3204083677&v=2.1&it=r&sid=BNCN&asid=c9303fb5 , (accessed 8 February 2021).

[iv] Henry fought in the 1815 Battle of New Orleans, in which he served under future American President Andrew Jackson. Henry kept in correspondence with Jackson until Jackson’s death. Source: https://www.loc.gov/search/?fa=contributor:palfrey,+henry+william&st=gallery (accessed 10/02/2021).

[v] Frank Otto Gatell, ‘Doctor Palfrey Frees His Slaves’, The New England Quarterly, (1961), Vol: 34, Issue: 1, pp. 74-86, pp. 80-81.

[vi] Palfrey Family Papers, Series 1, Letters of General Henry William Palfrey 1798 -- 1866, Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections, Special Collections, Hill Memorial Library, Louisiana State University Libraries, Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

[vii] Beckert, Empire of Cotton, p. 200.

[viii] Letters of General Henry William Palfrey 1798 – 1866.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] David Hepburn Milton, Lincoln’s Spymaster: Thomas Haines Dudley and the Liverpool Network, (Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books: 2003), p. 19.

[xi] David Seed (eds.), American Travellers in Liverpool, (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press: 2008), p. 82.

[xii] Loy, 10 Rumford Place, p. 355.

[xiii] Fraser, Trenholm & Co., Cotton Merchants collections, B/FT 1/137, W L Trenholm, New York (pp 6). He analyses condition of the defeated South during last 2 years of war, Maritime Archives and Library, Merseyside Maritime Museum, Liverpool

[xiv] White man’s burden is defined by Merriam-Webster as ‘the alleged duty of the white peoples to manage the affairs of the less developed nonwhite peoples’, Source: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/white%20man%27s%20burden , (accessed 11 February 2021).

[xv] Loy, 10 Rumford Place, p. 360.

[xvi] Fraser, Trenholm & Co., Cotton Merchants collections, B/FT 1/70, A Turner Porter (Rector of Church of Holy Communion), Charleston (pp 2, damaged.), Maritime Archives and Library, Merseyside Maritime Museum, Liverpool.

[xvii] FT 1/70, A Turner Porter (Rector of Church of Holy Communion), Charleston (pp 2, damaged.).

[xviii] Moody, The Persistence of Memory, p. 44.

Bibliography:

Allison, J., E., ‘The Development of Merseyside and the Port of Liverpool’, The Town Planning Review, (1953), Vol: 24, Issue: 1, pp. 52-76

Beckert, S., Empire of Cotton: A New History of Global Capitalism, (London: Penguin Books: 2015)

Connor, C., ‘Fraser, Trenholm & Company: The Confederate Cause in Liverpool’, in Davies, J., A., Hollinshead, J., E., (eds.), A Prominent Place: Studies in Merseyside History, (Liverpool: Liverpool Hope Press: 1999)

Cubitt, G., History and Memory (Historical Approaches), (Manchester: Manchester University Press: 2007)

Fraser, Trenholm & Co., Cotton Merchants collections, B/FT 1/137, W L Trenholm, New York (pp 6). He analyses condition of the defeated South during last 2 years of war, Maritime Archives and Library, Merseyside Maritime Museum, Liverpool

Fraser, Trenholm & Co., Cotton Merchants collections, B/FT 1/70, A Turner Porter (Rector of Church of Holy Communion), Charleston (pp 2, damaged.), Maritime Archives and Library, Merseyside Maritime Museum, Liverpool

Fraser, Trenholm & Co., Cotton Merchants collections, B/FT 6/30, Extracts from correspondence between the Commissioners of Customers and the Custom House Authorities at Liverpool re Alabama (vessel no 290), Maritime Archives and Library, Merseyside Maritime Museum, Liverpool.

Gatell, F., O., ‘Doctor Palfrey Frees His Slaves’, The New England Quarterly, (1961), Vol: 34, Issue: 1, pp. 74-86

Hall, N., ‘Liverpool’s Cotton Importers c. 1700 to 1914’, Northern History, (2017), Vol: 54, Issue: 1, pp. 79-93

Hall, N., ‘The Liverpool Cotton Market and the American Civil War’, Northern History, (1998), Vol: 34, Issue: 1, pp. 149-169

Hosgood, C., ‘The “Language of Business”: Shopkeepers and the Business Community in Victorian England’, Victorian Review, (1991), Vol: 17, Issue: 1, pp. 35-50

Jeremy, D., ‘Introduction: debates about interactions between religion, business, and wealth in Modern Britain’, in Jeremy, D. (eds.), Religion, Business and Wealth in Modern Britain, (Taylor & Francis Group: 1998)

Kilbride, D., ‘Travel Writing as Evidence with Special Attention to Nineteenth-Century Anglo-America’, History Compass, (2011) Vol: 9, Issue: 4, pp. 339-350

‘LAUNCH OF A GOVERNMENT TROOPSHIP AT BIRKENHEAD’, (24 November 1862), Liverpool Mercury, British Library Newspaper, Source: https://go.gale.com/ps/retrieve.do?tabID=Newspapers&resultListType=RESULT_LIST&searchResultsType=SingleTab&hitCount=1&searchType=AdvancedSearchForm¤tPosition=1&docId=GALE%7CBB3204051857&docType=Article&sort=Pub+Date+Forward+Chron&contentSegment=ZBLC-MOD1&prodId=BNCN&pageNum=1&contentSet=GALE%7CBB3204051857&searchId=R9&userGroupName=livjm&inPS=true , (accessed 11 February 2021)

Lovejoy P., E., and Richardson D., ‘African Agency and the Liverpool Slave Trade’, in Richardson, D., Schwarz, S., Tibbles, A. (eds.), Liverpool and Transatlantic Slavery, (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press: 2007)

Loy, W., ’10 Rumford Place: Doing Confederate Business in Liverpool’, The South Carolina Historical Magazine, (1997), Vol: 98, Issue: 4, pp. 349-374

Milton, D., H., Lincoln’s Spymaster: Thomas Haines Dudley and the Liverpool Network, (Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books: 2003)

Moody, J., The persistence of Memory: Remembering Slavery in Liverpool, ‘Slaving Capital of the World’, (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press: 2020)

Muir, R., History of Liverpool, (London: 1907)

Morgan, K., ‘Liverpool’s Dominance in the British Slave Trade, 1740–1807’, in Richardson, D., Schwarz, S., Tibbles, A. (eds.), Liverpool and Transatlantic Slavery, (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press: 2007)

Palfrey Family Papers, Series 1, Letters of General Henry William Palfrey 1798 -- 1866, Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections, Special Collections, Hill Memorial Library, Louisiana State University Libraries, Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Seed, D., (eds.), American Travellers in Liverpool, (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press: 2008)

Series 1, General Correspondence and Related Items, 1775-1885, Henry William Palfrey letters to Andrew Jackson, 1838-1843, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/search/?fa=contributor:palfrey,+henry+william&st=gallery , (accessed 11 February 2021)

‘SUMMARY’, (14 April 1863), Liverpool Mercury, British Library Newspaper, Source: https://go.gale.com/ps/retrieve.do?tabID=Newspapers&resultListType=RESULT_LIST&searchResultsType=SingleTab&hitCount=25&searchType=AdvancedSearchForm¤tPosition=9&docId=GALE%7CBB3204055798&docType=Article&sort=Pub+Date+Forward+Chron&contentSegment=ZBLC-MOD1&prodId=BNCN&pageNum=1&contentSet=GALE%7CBB3204055798&searchId=R2&userGroupName=livjm&inPS=true , (accessed 11 February 2021)

‘The American Civil War surrender on the Mersey’, 7 November 2015, BBC News, Source: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-merseyside-34725621 , (accessed 8 February 2021)

‘THE CONFEDERATE CRUISER SHENANDOAH IN THE MERSEY’, 7 November 1865, Liverpool Mercury, British Library Newspapers, Source: https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=BNCN&u=livjm&id=GALE|BB3204083580&v=2.1&it=r&sid=BNCN&asid=f23c98d0 (accessed 8 February 2021)

‘THE SHENANDOAH’ 9 November 1865, Liverpool Mercury, British Library Newspapers, Source: https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=BNCN&u=livjm&id=GALE|BB3204083677&v=2.1&it=r&sid=BNCN&asid=c9303fb5 , (accessed 8 February 2021)

‘White man’s burden definition’, Merriam-Webster, Source: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/white%20man%27s%20burden , (accessed 11 February 2021)